Seurat Pointillism: When Light Comes Alive in Your Eyes

- Teresa Perri

- 1 day ago

- 2 min read

Pointillism is that strange magic that happens when an artist stops painting like a man and starts thinking like a prism.

Pointillism was not born from a sudden romantic inspiration under a starry sky, but from a radical bet made in a dusty Paris studio around 1884.

Georges Seurat, a reserved man who preferred physics treatises over art critics, became convinced that traditional painting had an unavoidable limit: mud.

Every time a painter mixes two colors on a palette, light fades a little.

Blue mixed with yellow becomes green, beautiful but always duller than the original colors.

The Scientific Method Behind Seurat Pointillism

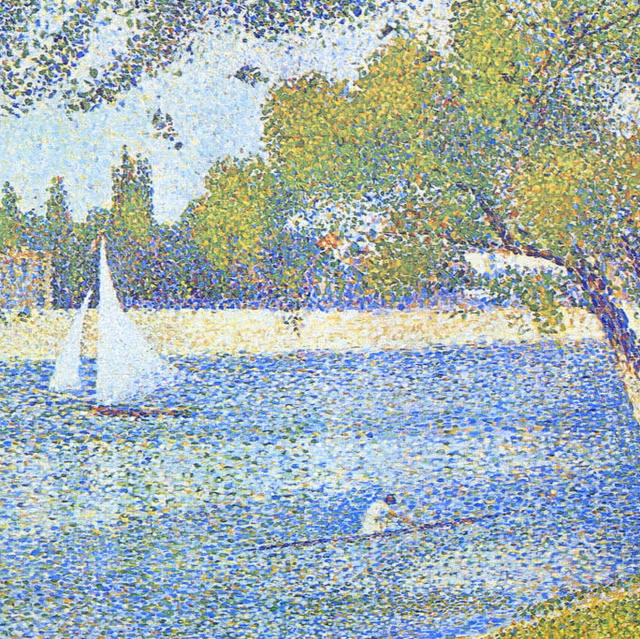

To overcome this limit, Seurat acted like a surgeon. He stopped spreading paint and started tapping it. He replaced the flowing hand with a vertical wrist movement, obsessively placing drops of pure light only millimeters wide.

This method, jokingly called “confetti painting,” is based on a physical law known as simultaneous contrast. When an orange dot is placed next to a blue one, the eye does not simply see two colors — it sees a spark.

The colors energize each other, vibrate, and create an illusion of brightness no chemical mixture could replicate. This is “optical mixing”: the artwork is not completed on the canvas, but on the viewer’s retina.

The Labor Behind A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte

There is enormous physical effort behind these paintings. To complete his most famous work, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, Seurat spent two years applying millions of tiny brushstrokes.

It was draining work, filled with silence and mathematical calculation to decide where to place each atom of pink or violet.

Paul Signac, his closest ally, pushed the technique further by using larger dots, turning the paintings into something similar to stained-glass windows hit by sunlight.

Why Seurat Pointillism Still Matters in the Pixel Era

Looking at these works, there is an unusual stillness. The figures are motionless, the profiles sharp, the trees sculptural. Time feels suspended.

The most astonishing fact is that these artists were speaking the language of the future without knowing it. Every time we zoom into a photo and see the tiny squares that compose it, we are witnessing the legacy of Seurat Pointillism.

Pixels are simply the technological descendants of those painted dots.

Pointillism reminds us that reality is made of fragments. That harmony is not built through a single grand gesture, but through patient repetition — placing one right element next to another, thousands of times, until they begin to shine together.

Comments